Tony Insall har bakgrunn blant annet som diplomat ved den britiske ambassaden i Oslo, og har tidligere forsket på forholdet mellom Arbeiderpartiet og det britiske Labour-partiet etter 1945. De siste årene har han spesialisert seg på etterretningshistorie fra andre verdenskrig.

En tysk Abwehr-offiser skaffet den britiske etterretningstjenesten Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) opplysninger om nazistenes invasjonsplaner av både Tsjekkoslovakia i 1938 og Storbritannia i 1940. Dobbeltagenten var imidlertid ikke i posisjon til å varsle om tyskernes angrep på Norge og Danmark.

TVUNGET TIL Å TENKE NYTT

I London dukket det likevel stadig opp informasjon fra ulike kilder om den forestående operasjon Weserübung, men spredt og lite spesifikk. I tillegg ble etterretningen sendt til ulike mottakere i det britiske regjeringsapparatet. Ingen så det samlede bildet i tide til å dra de rette konklusjonene.

– Alliert etterretning om den tyske invasjonen av Norge ble ikke godt nok utnyttet. Hendelsen tvang britene til å tenke nytt om håndteringen av etterretningsinformasjon, forteller den britiske historikeren Tony Insall.

Han har bakgrunn blant annet som diplomat ved den britiske ambassaden i Oslo, og har tidligere forsket på forholdet mellom Arbeiderpartiet og det britiske Labour-partiet etter 1945. De siste årene har han spesialisert seg på etterretningshistorie fra andre verdenskrig.

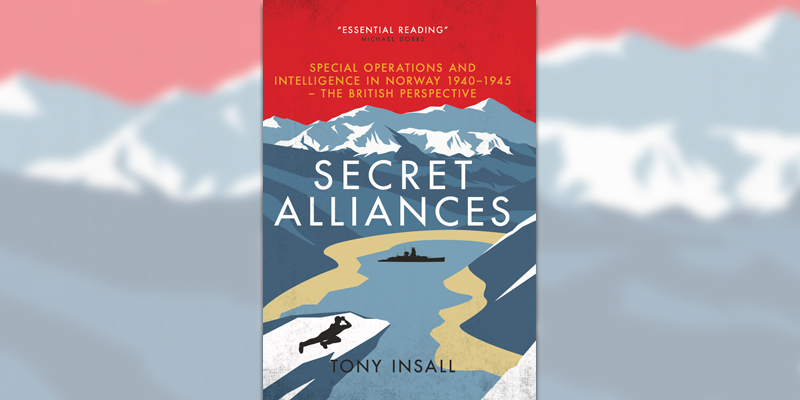

Fra venstre: Nordmennene Ruben Langmo, Simon Sinclair Fjeld og Olav Martin Leirvåg, som deltok i den første allierte sabotasjeaksjonen i det tysk-okkuperte Norge, med briten James Chaworth-Musters fra SOE. Foto: Scalloway Museum.

SKEPSIS TIL NORDMENNENE

SIS opplevde også et annet tilbakeslag tidlig i krigen. Det hemmelige agentnettverket tjenesten hadde bygget opp over store deler av Europa gikk i oppløsning ved den tyske okkupasjonen av flere stater. Arbeidet måtte startes forfra. Det var et stort behov for presis kunnskap om tyskernes aktivitet og planlegging på en rekke områder.

De første norske skrittene for å få til et formelt samarbeid med SIS ble tatt sommeren 1940 ved å organisere et eget etterretningskontor som lå under Utenriksdepartementet. Det ble senere kjent som FOII etter at eksilregjeringen gjenopprettet Forsvarets Overkommando i februar 1942.

Men både SIS og britenes militære spesialenhet Special Operations Executive (SOE) hadde sin mistro angående nordmennenes pålitelighet. – Ingen av tjenestene ønsket i starten å samarbeide særlig tett eller dele for mye informasjon med sine norske allierte, sier Insall.

Nordmannen og agenten Olav Wallin stod sensommeren 1940 sannsynligvis for den første motstandsmeldingen fra det tysk-okkuperte Europa til Storbritannia. (Foto: Rosemary Wallin)

En tidlig SOE-vurdering var at nordmennene «som folk var notorisk udisiplinerte og pratsomme». Så lenge de hadde norske eksilmyndigheters tilslutning til å iverksette operasjoner på norsk jord, foretrakk SIS og SOE for det meste å arbeide uavhengig. De rekrutterte sine egne agenter blant de som hadde flyktet fra Norge etter at landet ble okkupert.

GRADVIS OPPBYGGING

Det var først når agentene tilbake i Norge begynte å formidle gode rapporter at tilliten ble sterkere. Etableringen av en militær britisk-norsk samarbeidskomité tidlig i 1942 var også et viktig steg i å forbedre relasjonene mellom SOE og nordmennene.

– Begge parter hadde mye å lære, spesielt om opptrening, sikkerhet og kommunikasjon, forteller Insall. – I den tidlige fasen mislyktes mange forsøk på å opprette radiokontakt mellom Norge og London.

– Nettverket tok tid å bygge opp igjen, og pålitelige opplysninger begynte ikke å komme før sent i 1941 og da fortsatt i ganske liten skala, sier Insall, som har skrevet boken Secret Alliances om spesialoperasjoner og etterretningsarbeid i Norge under andre verdenskrig.

SIS klarte å skape et nytt agentnettverk over hele landet, som gjorde tjenesten i stand til å kartlegge bevegelsene til de store tyske krigsskipene i norsk farvann. Rapporteringen fra SIS sine spionasjestasjoner ble et viktig supplement til Ultra, de alliertes system for kodeknekking.

NSBs administrasjonsbygg i ruiner etter å ha blitt sprengt av Oslogjengen 15. mars 1945 under ledelse av SOE-agent Gunnar Sønsteby. (Foto: Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum)

SUKSESSER

– Etterretningen fra felten i Norge var uvurderlig, mener Insall. – Høydepunktet var de avgjørende rapportene om det tyske slagskipet Tirpitz, helt fram til det ble senket av britiske bombefly utenfor Tromsø 12. november 1944.

SIS var avhengig av å operere i fred og ro for å være effektive, mens SOE skapte andre forhold med sine sprengningsaksjoner.

– Oppdragene som SOE utførte i Norge endret seg med krigens utvikling, forteller Insall. – Enkeltstående sabotasjer var ment som nålestikk for å skape uro i den tyske okkupasjonsstyrken, men dette skjedde samtidig med et fokus på å skaffe etterretningsinformasjon. Det ga noen ganger fremragende resultater, som også SIS satte stor pris på.

Senere skiftet prioriteringen tilbake igjen til større sabotasjeoppdrag som skulle påvirke den tyske krigsinnsatsen, fra å ødelegge produksjonsanlegg til å forhindre transporten av mineraler fra Norge til kontinentet.

– Hovedsuksessen til SOE i Norge var selvfølgelig Operasjon Gunnerside i februar 1943, sier Insall. – Sabotørgruppen ledet av Joachim Rønneberg lyktes i å sprenge tungtvannsfabrikken på Vemork og sette den ut av drift i et halvt år.

Samarbeidet mellom SOE og Milorg ble også tettere. Den norske militære motstandsbevegelsen fikk stadig mer hjelp med materiell og opptrening til å forberede frigjøringen av landet.

TAP OG TILBAKESLAG

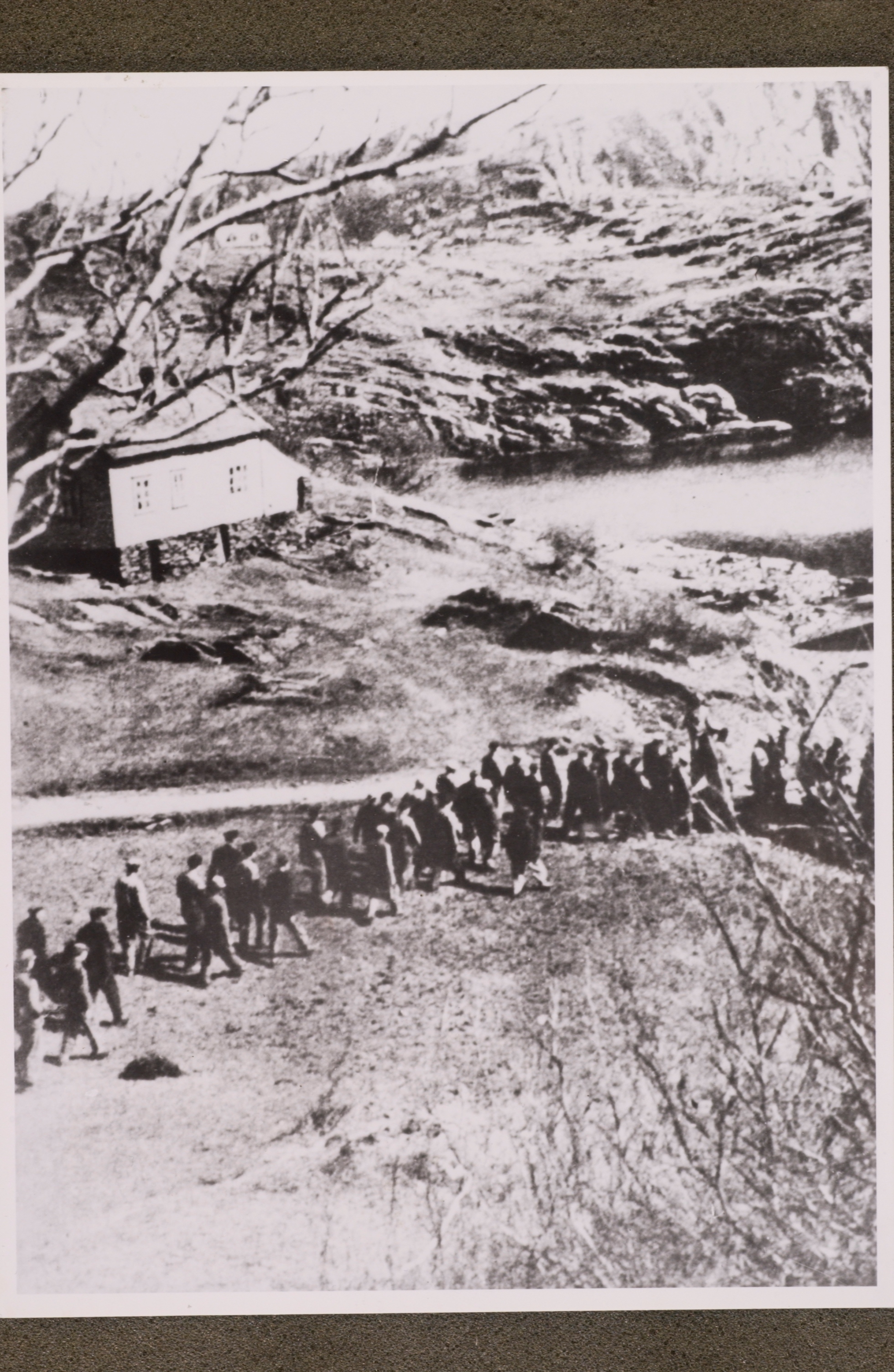

Den største enkeltstående tragedien for begge tjenestene i Norge var Telavåg-affæren i april 1942. Både SIS og SOE ilandsatte folk i samme område på Vestlandskysten løpet av få dager, og tiltrakk seg okkupantens oppmerksomhet. I raidet som fulgte drepte SOE-agenter to tyskere, en av dem en høytstående Gestapo-offiser. Tyskerne gjengjeldte ved å brenne bygda og deportere innbyggerne. De fleste mennene ble sendt til Sachsenhausen, hvor 31 av dem døde. Resten ble sendt til ulike leirer i Norge.

– Tap og tilbakeslag var uunngåelige i motstandsvirksomhet, som regel som følge av enten usikkerhet, ignoranse, naivitet, svik eller ren uflaks, sier Tony Insall. – Den kanskje verste konsekvensen av uforsiktighet var undervurderingen av tysk radiopeiling, som førte til tapet av tolv SIS-stasjoner i 1944, og trolig alle de som ble avslørt i 1945. SOE sine stasjoner var ofte mer mobile og led ikke fullt så mye av denne trusselen.

Nesten tretti av totalt over 200 norske SIS-agenter mistet livet under krigen, sammenlignet med omtrent 50 av 530 nordmenn som jobbet for SOE.

Telavågs mannlige befolkning føres bort. De ble sendt til konsentrasjonsleiren Sachsenhausen, der 31 av dem døde. Foto: Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum.

VIKTIG ROLLE

– Vi må heller ikke tro at britene hadde monopol på etterretningssuksesser under krigen, fortsetter Insall. – Tyskerne oppnådde sine seirer også her. B-Dienst, en avdeling av marinens etterretningstjeneste, var i stand til å registrere rundt 30 prosent av trafikken til britiske og franske krigsskip under felttoget i Norge i 1940, nok til å skaffe seg et klart bilde av flåteforflytninger i Nordsjøen. Men den tyske tjenesten var ikke i nærheten av å være så effektiv som kodeknekkerne i Bletchley Park, stedet der britene samlet sine etterretningsressurser.

Insall mener effektiviteten til en lang rekke av etterretnings- og sabotasjeoperasjonene utført i Norge under krigen i høyeste grad tåler sammenligning med det som ble oppnådd i andre okkuperte land i Europa.

– Den hemmelige virksomheten bidro til å gjøre stor skade på tyskernes evne til å føre krig, sier den britiske historikeren. – Den var med på å opprettholde Hitlers frykt for en invasjon i nord og utplasseringen av store troppestyrker i Norge, svekket tysk sjømakt, forsinket transporten av krigsviktige naturressurser og forstyrret ubåttrafikken fra norskekysten ut i Atlanterhavet, for å nevne noe.

– De allierte kunne ikke ha vunnet andre verdenskrig hvis de ikke først hadde vunnet etterretningskrigen. Etterretning var avgjørende på et strategisk og også på et taktisk nivå, selvfølgelig avhengig av hvordan den ble brukt. Historikere vil uten tvil fortsatt være uenige om den eksakte betydningen av ulik etterretningsinformasjon – den pågående debatten om Ultras betydning for krigen i Atlanterhavet er et tydelig eksempel – men det vil ikke endre på vårt syn på etterretningens overordnede verdi, avslutter Insall.

TONY INSALL Q&A

In your view, to what extent did intelligence affect or determine the development and outcome of the Second World War on an overall level?

– The allies could not have won the Second World War if they had not first won the intelligence war. Intelligence on both a strategic and a tactical level was crucial. It provided insights both into what the Axis leaders were thinking strategically, and also provided commanders with tactical intelligence about what the enemy was planning. In the European theatre, much of this intelligence came from Ultra signals intelligence provided mainly by the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, while elsewhere the Americans made a major contribution. A good example of the value of strategic intelligence was provided by reports back to his government from Hiroshi Oshima, the Japanese military attaché in Berlin, decyphered by GC&CS. General George Marshall described Oshima as ‘our main basis of information regarding Hitler's intentions in Europe’. Admiral Cunningham’s victory against the Italians at Matapan was not won by Ultra: it still required clear and imaginative leadership. But Ultra gave him a decisive tactical advantage by telling him about Italian dispositions so that he could plan interceptions.

Historians will no doubt continue to differ over the precise significance of particular streams of intelligence – the current debate over the value of Ultra to the war in the Atlantic is a case in point – but that will not change our view of its overall value.

It was a formidable achievement by the agencies responsible to arrange for the circulation and use of this material both by ministers and commanders in the field, while ensuring that it was not used in a way which threatened its security. The secret of Ultra was kept until long after the war and staff never talked about their work. Churchill said of GC&CS that ‘they were the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled’.

Incidentally, we should not think that the British and their allies had a monopoly of success with signals intelligence. The Germans had their achievements too. For example B-Dienst, their naval intercept service, was able to read some 30% of British and French naval traffic during the campaign following the invasion of Norway in April 1940, enough to be able to gain a clear picture of British naval movements in the North Sea. And Henry Denham, the British naval attaché in Stockholm who famously received the first warning about the movements of the Bismarck from his Norwegian colleague Ragnvald Roscher Lund in May 1941, was mortified after the war to discover in German naval archives an intercepted and decyphered copy of his reporting telegram to the Admiralty. So the Germans knew that we knew about the Bismarck’s movements, though that does not appear to have led them to change their plans. But the German service was nowhere near so consistently effective as the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park.

Human intelligence was important too. But it could not often match this kind of coverage.

Were the British intelligence services adequately informed about the developments in Norway and Scandinavia at the outbreak of war in 1939 and in the run-up to the German invasion in April 1940?

– SIS, the British Secret Intelligence Service, did have access to an agent who was able to provide reporting on German intentions concerning their planned invasions of several countries. This was Paul Thümmel, an Abwehr officer initially recruited by the Czechs who gave them advance warning of the invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939. The Czechs shared his intelligence with SIS. During 1940, Thümmel provided plenty of accurate intelligence about German preparations to invade Britain, and about a variety of postponements, including one concerning an invasion scheduled for May 1940, which was due to the fact that all available troops were then being used in Norway. He reported in December that Hitler had decided on a further postponement, perhaps until the end of March 1941 – and by then of course the German focus had changed.

While Thümmel was not in a position to provide intelligence on German plans for Norway and Denmark, there was a wealth of other reporting available, mainly from SIS. Unfortunately, none of it was as specific and clear as the sort of intelligence provided by Thümmel in the examples I have given. Moreover, depending on the subject, the intelligence was distributed to a wide cross section of recipients in different service departments and the Foreign Office, and was not generally shared. No one section or department saw all the reporting, and there was no structure in existence at that time capable of assessing all available intelligence in a timely manner and drawing appropriate conclusions. So the failure to anticipate the German invasion was caused not so much by a failure to provide relevant intelligence, as by a widespread failure to distribute and assess it properly. One positive outcome of the German invasion of Norway was that it forced changes on the central government machinery for dealing with intelligence, which left it much better equipped to make use of the growing volume of intelligence which would become available over the next five years.

How much emphasis did the British put on creating a secret intelligence network in Norway in the wake of the German invasion and occupation?

– The agent networks which had been built up by SIS before the war, both in Norway and elsewhere in German-occupied Europe, were disrupted by the German invasion, and it was necessary to start afresh. The requirement for good intelligence about German activities and intentions in a wide range of fields was very urgent. As early as November 1939 the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division had specified its urgent need to know about the activities of the more important German naval units and their movements and those of merchantmen carrying iron ore along the Norwegian coast, as well as the building programmes for the Bismarck and other major warships. Frank Foley, posted from Berlin to Oslo, achieved a few small successes, for example with a rudimentary coast-watching system, but the German invasion of Norway brought that work to an abrupt halt.

Initial progress to reestablish the networks was frustratingly slow, and it took time to build up satisfactory coverage. Good intelligence only really began to become available in late 1941, and even that was still on a fairly small scale.

How did the intelligence cooperation come about and how did it work? And what about the initial British mistrust concerning the reliability and loyalty of the Norwegians?

– The first steps were taken by Halvdan Koht. In late July 1940, he met Eden, then Secretary of State for War, and Beaumont-Nesbitt, the Director of Military Intelligence, and obtained their agreement to arrange for Norwegian contact with SIS. He then asked Sverre Midtskau, a young Army lieutenant, to set up an intelligence office, initially known as Utenriksdepartementet Etteretningskontor or UD/E, later FO.II. Koht participated in some of the early meetings between Midtskau and Frank Foley, when they worked out their objectives for cooperation. This required some compromise, because SIS was mainly interested in military intelligence with a particular emphasis on naval activities, whereas the Norwegians wanted reliable information about political developments in Norway. Koht and Foley also agreed that the costs would be shared equally between them, and signed a memorandum to that effect.

SIS, like SOE, initially had misgivings about the reliability and sobriety of the Norwegians they worked with. An early SOE judgement of the Norwegians was that they ‘as a people they are notoriously ill-disciplined and are great talkers’. Neither service initially wanted to cooperate very closely or share too much information with their Norwegian partners. As long as they had Norwegian consent for their activities, they preferred to work largely independently and to recruit their own agents from among refugees who had fled from Norway. The situation gradually started to change once Finn Nagell, whose journey was arranged through the ill-fated Oldell station, arrived in Britain in November and took over responsibility for UD/E, and when Martin Linge took up a similar position liaising with SOE. But both sides still had plenty to learn, particularly about training, security and communications. There were too many cases in the early stages where, after a station had been painstakingly established, faulty radios or crystals or difficulties with transmission schedules meant that it could not make contact with London – at least four radios failed to function during this early period. Once stations began to be established and to report good intelligence, trust grew and cooperation became closer. The establishment of the Anglo Norwegian Collaboration Committee (ANCC) in early 1942 marked a key step in improving relations between SOE and the Norwegians.

SOE conducted operations in Norway in which Norwegian commandos under British command were engaged. What kind of missions did they carry out?

– Their tasking changed as SOE and British policy changed, so they carried out quite a wide range of operations. Some of the initial sabotage missions, while successful, were little more than pinpricks intended to harass the German occupying forces. Others, particularly the first trip by Odd Starheim in early 1941, focussed more on intelligence collection – much appreciated by SIS at a time when they had few sources of their own. They also participated in some of the main Combined Operations raids on the Norwegian coast, including Operation Archery against Måløy, where the charismatic Martin Linge was killed. Thereafter, the focus shifted much more towards sabotage against targets whose destruction would degrade the German war effort, for example destroying the means of production or preventing the export of precious minerals from Norway, or attacking factories or other key installations, blowing up fuel dumps or disrupting other supplies for German U-boats, or sinking shipping. They began to work more closely with Milorg, the home-based resistance organisation, focussing on preparations to support the liberation of Norway by training and equipping plenty of Norwegian volunteers. They also set up teams whose task would be to protect key elements of the Norwegian infrastructure, power points and ports for example, if the Germans attempted to destroy them.

Their main achievement, of course, was operation Gunnerside, when a small group of saboteurs led by Joachim Rønneberg, successful destroyed the plant producing heavy water at Vemork, putting it out of action for six months.

The Norwegian resistance established its own network of agents, who reported directly to Norwegian authorities-in-exile in Stockholm and London. They would sometimes operate with SIS agents. How did this interaction work?

– The network developed by SIS and FO.II to provide intelligence reporting from Norway was not the only intelligence organisation functioning there during the occupation. There were more than a dozen others. The largest was XU, which had approximately 1,500 agents in southern Norway and had achieved country-wide coverage by 1943, providing a wealth of political and military intelligence. Although SIS would have been willing to cooperate with it as it did with FO.II, the Norwegians preferred to keep it separate, though SIS did provide assistance with training. However, an exception was the close cooperation over contact with XU agents, usually students, living in Germany. SIS was permitted to exploit their potential either as sources of intelligence in their own right, or as channels of communication to pass on information from their own German agents who were working there. It is not surprising that such intelligence would have been of considerable interest to SIS, who found it difficult to run sources in Germany. In such cases, they paid all the costs which were involved. The growth of this work, and the scale of XU reporting from Norway, led to a great increase in the work of MI.II in Stockholm. SIS therefore arranged to second a Norwegian speaking British officer, John Turner, to work in MI.II in Stockholm and to facilitate liaison. He used the alias John Pettersen and represented himself as a Norwegian. This arrangement worked well, one might say profitably, until it came to light that Turner was being paid both by SIS and also by XU! An irritated SIS told him to stop taking a salary from XU forthwith.

What were the most outstanding successes and failures of the Norwegian-British intelligence operations during the war?

– The greatest intelligence success of SIS and its Norwegian agents was the network which it painstakingly built up over the entire country, which it enabled it to provide coverage of the movements of all major German warships in Norwegian waters. At the end of the war Finn Nagell, head of FOII, the Norwegian intelligence office, was able to claim that SIS agents provided reporting which to a greater or lesser extent contributed to the sinking of the Bismarck, Scharnhorst and Tirpitz, and also to the damage caused to the Prinz Eugen, Hipper and Scheer. (The torpedo attack on the Lützow off Egersund in June 1941, which caused serious damage, was entirely attributable to Ultra.) Edward Thomas, an officer who worked in both naval intelligence and GC&CS, observed after the war that Ultra was seldom complete and often late. He added that the reporting of SIS coastwatching stations was a very important supplement to Ultra, and regularly provided the first intelligence about German naval movements to be received in London. Its value could not be overestimated. The greatest highlight was the extent of reporting about Tirpitz – there are 145 reports in Admiralty files about its status and movements between January 1942 and November 1944 when it was in Norway - which also included regular and frequent weather reports from agents when air attacks were being launched, despite the risk of their being located by German direction finding. That represented bravery of a high order.

Norwegian agents also produced plenty of reporting leading to the sinking of German merchant shipping, often carrying valuable minerals from Norway to Germany. As a result, for example, iron ore shipments declined from 40,000 tons a month in October 1943 to 12,000 tons in November 1944.

The nature of SIS work, in the shadows, meant that their failures tended to be less obvious than those of SOE. SIS needed peace and quiet to be effective, while SOE created quite the opposite – though the number of SIS agents who lost their lives, nearly 30, was a slightly higher percentage than that of those Norwegians working for SOE. Perhaps the biggest single disaster was that at Telavåg in April 1942, when separate fishing boats delivered SIS and SOE agents to the same area within a few days of each other, attracting German attention. During their raid which followed, SOE agents killed two Germans, one of whom was a senior Gestapo officer. The Germans retaliated by blowing up the entire village, and deporting all the inhabitants, sending many of the men to Sachsenhausen (where 31 of them died), and the rest to camps in Norway.

Losses and setbacks are inevitable in resistance activities, usually resulting from either insecurity, ignorance, naivety, betrayal or sheer bad luck. Perhaps the worst consequence of ignorance was the inability of SIS and their Norwegian counterparts to understand the threat to their stations from German direction finding, which led to the loss of twelve stations in 1944, and probably all of those lost in 1945 too. SOE, whose stations could sometimes to be more mobile, did not suffer quite so much from this problem.

One review of your book argues that “Norwegians made a significant contribution to a wide range of Allied intelligence operations, with an impact extending far beyond Scandinavia”. Can you elaborate on this?

– Combined Operations raids, as well as SOE operations on the Norwegian coast encouraged the Germans to think that an invasion of Norway was a continuing possibility, and led them to station a significant number of troops there, up to 400,000. The subsequent sabotage by both SOE and Milorg of railway links in late 1944 and 1945 helped to ensure that many of them remained there and were unavailable to help reinforce German troops fighting on the Western front. Intelligence from SIS coast watching stations led to the sinking or damage of quite a few German warships and a serious weakening of German naval power, which freed up elements of the Royal Navy, enabling them to deploy to the Far East or other locations where they were also needed. Norwegian agents participating in the extensive and very successful ‘Doublecross’ operation worked as double agents and helped to fool the Abwehr with misleading information in a productive case which lasted over three years. SOE sabotage operations helped to degrade the German war effort in many different ways, for example by depriving them of badly needed minerals required for construction projects or the assembly of essential military equipment back in Germany, or disrupting the operations of U-boats deploying from Norway into the Atlantic.

The effectiveness of the wide range of intelligence and sabotage operations undertaken in Norway more than stand comparison with those achieved in other countries in occupied Europe, in the extent to which they damaged the German ability to wage war.

And, while it was not linked to intelligence operations, we should not overlook the enormous contribution to the allied war effort made by Norwegian shipping. Ships from Norway helped make up for the nearly crippling losses caused by U-boats to Atlantic convoys, which were bringing greatly needed supplies to Britain from the United States. In the course of the war, Norway lost over two million tons of shipping – half its total tonnage - as well as more than 3,600 seaman and passengers.